Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment (Chapter5)

by5 - Standard I/O Library

Introduction

This library is specified by ISO C standard, implemented on many operating systems other than UNIX System. Additional interfaces are defined as extensions to ISO C by Single UNIX Specification.

Standard I/O library handles details such as buffer allocation and performing I/O in optimal-sized chunks (obviating need to worry about using correct block size). Makes library easy to use, but introduces another set of problems.

Streams and FILE Objects

We saw a little bit this on Chapter3. When file is opened, file descriptor is returned, and descriptor is used for subsequent I/O operations. With standard I/O discussion centers on streams. When we open or create a file with standard I/O library, we’ve associated a stream with the file.

With ASCII, a single character is a single byte. With internation character sets, character can be more than one byte. Standard I/O streams can be used with single-byte and multibyte (or wide) characters. A stream’s orientation determines whether characters are read and written are single or multibyte. When a stream is created has no orientation. If multibyte I/O function (*

#include <stdio.h>

#include <wchar.h>

int fwide (FILE *fp, int mode);

Returns: positive if stream is wide oriented

negative if is byte oriented

0 if no orientation

fwide performs different tasks, depending on value of mode argument.

- If mode is negative, fwide will try to make specified stream byte oriented.

- If mode is positive, fwide will try to make specified stream wide oriented.

- If mode is zero, fwide will return value identifying stream’s orientation.

fwide will not change orientation of a stream that is already oriented. Also there’s no error return. So only thing we can do is to crear errno before calling fwide and check value after return. On the book we will deal only with byte-oriented streams.

When we open a stream, standard I/O function fopen retruns a pointer to FILE object. This is a structure that contains all information required by standard I/O library to manage the stream: file descriptor, pointer to a buffer for the stream, size of buffer, count of number of characters currently in the buffer, error flag, etc. Application software should never need to examine FILE object, we pass FILE pointer as argument to each standard I/O function. We’ll refer to a pointer to FILE object, type FILE *, as a file pointer. We describe standard I/O library in context of a UNIX system. This library has been ported to a wide variety of other operating systems. We will talk about implementation on a UNIX system.

Standard Input, Standard Output, and Standard Error

Three streams predefined and available to a process: standard input, output and error. These refer to same files as the file descriptors STDIN_FILENO, STDOUT_FILENO and STDERR_FILENO.

These three standard I/O streams are referenced through predefined file pointers stdin, stdout, stderr. File pointers are defined in *

Buffering

Goal of buffering provided by standard I/O library is to use minimum number of read and write calls. Also library tries to do its buffering automatically for each I/O stream, obviating the need for application to worry about it. Unfortunately, single aspect of standard I/O library that generates most confusion is its buffering. Three types of buffering are provided:

-

Fully buffered. Actual I/O takes place when standard I/O buffer is filled. Files residing on disk are normally fully buffered by standard I/O library. Buffer used is usually obtained by one of standard I/O functions calling malloc first time I/O is performed on a stream. Term flush describes writing of a standard I/O buffer. A buffer can be flushed by standard I/O routines, such as when buffer fills or we can call the function fflush to flush a stream. In UNIX environment, flush means two different things. In terms of standard I/O library, it means writing out the contents of a buffer, which may be partially filled. In terms of terminal driver, such as tcflush function, it means to discard data that’s already stored in a buffer.

-

Line buffered. Standard I/O library performs I/O when a newline character is encountered on input or output. Allows us to output a single character at a time (with standard I/O fputc), knowing that actual I/O will take place only when we finish writing each line. Line buffering is used on a stream when it refers to a terminal (standard input and output). Line buffering comes with two caveats. First, size of buffer that standard I/O library uses to collect the line is fixed, so I/O might take place if we fill this buffer before writing a newline. Second, whenever input is requested through standard I/O library from an unbuffered stream or a line-buffered stream (that requires data to be requested from kernel) all line-buffered output streams are flushed. Reason for qualifier on line-buffered is that requested data may already be in buffer, which doesn’t require data to be read from kernel. Obviously, any input from unbuffered stream, requires data to be obtained from kernel.

-

Unbuffered. Standard I/O does not buffer characters. If we write 15 characters with standard I/O fputs function, 15 characters are expected to be output as soon as possible, probably with write function we saw in chapter 3. Standard error stream, is normally unbuffered so any error messages are displayed as quickly as possible, regardless of whether they contain a newline.

ISO C requires following buffering characteristics:

- standard input and standard output fully buffered, if and only if they don’t refer to an interactive device.

- standard error is nevery fully buffered.

This doesn’t tell whether standard input and standard output are unbuffered or line buffered if they refer to an interactive device and whether standard error should be unbuffered or line buffered. Most implementations default to following types of buffering:

- Standard error always unbuffered.

- All other streams are line buffered if they refer to terminal device; otherwise, they are fully buffered.

This standard is the one used of the platform tested on this book.

We will explore standard I/O buffering later.

If we don’t like defaults for any given stream, we can change buffering by calling setbuf or setvbuf:

#include <stdio.h>

void setbuf(FILE *restrict fp, char *restrict buf);

int setvbuf(FILE *restrict fp, char *restrict buf, int mode,

size_t size);

Returns: 0 if OK, nonzero on error

Functions must be called after stream has been opened, but before any other operation is performed on stream.

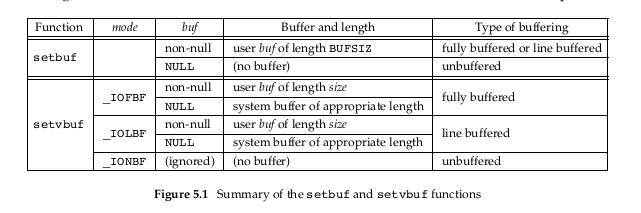

With setbuf, we can turn buffering on or off. To enable buffering, buf must point to a buffer of length BUFSIZ, constant defined in *

With setvbuf, we specify which type of buffering we want, done with mode argument, that can be:

- _IOFBF fully buffered

- _IOLBF line buffered

- _IONBF unbuffered

If we specify unbuffered stream , buf and size are ignored. If we specify fully buffered or line buffered, buf and size can optionally specify a buffer and its size. If stream is buffered and buf is NULL, standard I/O library will allocate its own buffer of the appropiate size for stream. By appropiate size, we mean value specified by BUFSIZ.

If we allocate a standard I/O buffer as automatic variable within a function, we have to close the stream before returning from function (because it would be on the stack). Some implementations use part of buffer for internal bookkeeping, so actual number of bytes of data that can be stored in buffer can be less than size . We should let the system choose buffer size and allocate the buffer. When we do this, standard I/O library automatically releases buffer when we close the stream. At any time, we can force a stream to be flushed.

#include <stdio.h>

int fflush(FILE *fp);

Returns: 0 if OK, EOF on error

fflush function causes any unwritten data for stream to be passed to kernel. As special case, if fp is NULL, fflush causes all output streams to be flushed.

Opening a Stream

fopen, freopen and fdopen open a standard I/O stream.

#include <stdio.h>

FILE *fopen(const char *restrict pathname, const char *restrict type);

FILE *freopen(const char *restrict pathname, const char *restrict type,

FILE *restrict fp);

FILE *fdopen(int fd, const char *type);

All three return: file pointer if OK, NULL on errors

Differences in three functions:

- fopen opens specified file.

- freopen opens a specified file on specified stream, closing stream first if it is already open. If stream previously had an orientation freopen clears it. Function is typically used to open a specified file as one of predefined streams: standard input, standard output, or standard error.

- fdopen takes existing file descriptor, which we could obtain from open, dup, dup2, fcntl, pipe, socket, socketpair or accept, and associates a standard I/O stream with descriptor. Used with descriptors returned by functions that create pipes and network communication channels. Because special type of files cannot be opened with standard I/O fopen, we have to call device-specific function to obtain a file descriptor, then associate stream using fdopen.

fopen and freopen are part of ISO C; fdopen is part of POSIX.1, since ISO C doesn’t deal with file descriptors.

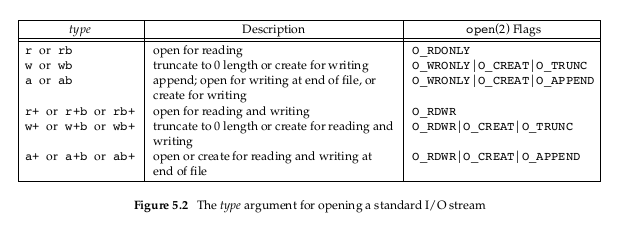

ISO C specifies 15 values for type (From Figure 5.2) Using character b as part of type allows standard I/O to differentiate between text file and binary file. As UNIX kernel doesn’t differentiate between these types, specifying b as part of type has no effect. With fdopen, meanings of type differ slightly. Descriptor has already been opened, so opening for writing does not truncate file. Also, standard I/O append mode cannot create file (since file has to exist if a descriptor refers to it). When file is opened with type of append, each write will take place at current end of file. If multiple processes open same file with standard I/O append, data from each process will be correctly written to file.

(Old versions from fopen didn’t handle append mode correctly, those version did lseek to end of file when stream was opened, to correctly support append mode when multiple processes are involved, file must be opened with O_APPEND flag, doing lseek before each write won’t work).

When file is opened for reading and writing (plus sign in type), two restrictions apply:

- Output cannot be directly followed by input without intervening fflush, fseek, fsetpos or rewind.

- Input cannot be directly followed by output without intervening fseek, fsetpos, or rewind, or input operation that encounters end of file.

| Restriction | r | w | a | r+ | w+ | a+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| file must already exist | + | + | ||||

| previous contents of file discarded | + | + | ||||

| stream can be read | + | + | + | + | ||

| stream can be written | + | + | + | + | + | |

| stream can be written only at end | + | + |

If new file is created specifying type of w or a, we’re not able to specify file’s access permission bits, as we did with open or creat in Chapter3. POSIX.1 requires implementations to create file with following permission bit set:

| *S_IRUSER | S_IWUSER | S_IRGRP | S_IWGRP | S_IROTH | S_IWOTH* |

We can restrict permissions by adjusting our umask value.

An open stream is closed by calling fclose

#include <stdio.h>

int fclose(FILE *fp);

Returns: 0 if OK, EOF on error

Any buffered output data is flushed before file is closed. Any input data may be buffered is discarded. If standard I/O library had automatically allocated a buffer for stream, buffer is released. When a process terminates normally, calling exit function or returning from main, all standards I/O streams with unwritten buffered data are flushed and all open standard I/O streams are closed.

Reading and Writing a Stream

Once we open a stream, we chan choose three types of unformatted I/O:

- Character-at-a-time I/O. Read one character at a time, with standard I/O functions handling all buffering, if stream is buffered.

- Line-at-a-time I/O. Read or write a line at a time, we use fgets and fputs. Each line is terminated with newline character, and we have to specify maximum line length that we can handle when we call fgets.

- Direct I/O. This type of I/O supported by fread and fwrite functions. For each I/O operation, we read or write some number of objects, where each object is of specified size. These functions are often used for binary files where we read or write a structure with each operation.

Input Functions

Three functions allow us to read one character at a time:

#include <stdio.h>

int getc(FILE *fp);

int fgetc(FILE *fp);

int getchar(void);

All three return: next character if OK, EOF on end of file or error.

Function getchar defined to be equivalent to getc(stdin). Difference between getc and fgetc is getc can be implemented as a macro, and fgetc doesn’t. This means 3 things:

- Argument to getc should not be an expression with side effects, because it could be evaluated more than once.

- fgetc is guaranteed to be a function, we can take its address. This allows us to pass address of fgetc as argument to another function.

- Calls to fgetc probably take longer than calls to getc, as it usually takes more time to call a function.

These three functions return next character as unsigned char converted to int. Reason for specifying unsigned is so that high-order bit, if set, doesn’t cause return value to be negative. Reason for requiring integer return value is that all possible character values can be returned, along with indication that either an error ocurred or end of file has been encountered. Constant EOF in *

Note these functions return same value whether an error occurs or the end of file is reached. To distinguish between the two, we must call ferror or feof.

#include <stdio.h>

int ferror(FILE *fp);

int feof(FILE *fp);

Both return: nonzero(true) if condition is true, 0 (false) otherwise

void clearerr(FILE *fp);

In most implementations, two flags are maintained for each stream in FILE object:

- An error flag.

- An end-of-file flag.

Both are cleared calling clearerr.

After reading from a stream, we can push back characters calling ungetc.

#include <stdio.h>

int ungetc(int c, FILE *fp);

Returns: c if OK, EOF on error

Characters that are pushed back are returned by subsequent reads on stream in reverse order of their pushing. Although ISO C allows an implementation to support any amount of pushback, an implementation is required to provide only a single character of pushback.

Character that we push back does not have to be same character that was read. We are not able to push back EOF. When we reach end of file, however, we can push back a character. Next read will return that character, and read after read after that will return EOF. This works because successful call to ungetc clears end-of-file indication for the stream.

Pushback is often used when we’re reading an input stream and breaking input into words or tokens. Sometimes we need to peek at next character to determine how to handle current character. It’s then easy to pùsh back character that we peeked at, for next call to getc to return. If standard I/O library didn’t provide this pushback capability, we would have to store character in a variable of our own, along with a flag telling us to use this character instead of calling getc next time we need a character.

Output Functions

Available that correspond to each of input functions we’ve already described.

#include <stdio.h>

int putc (int c, FILE *fp);

int fputc (int c, FILE *fp);

int putchar(int c);

All three return: c if OK, EOF on error

putchar is equivalent to putc(c, stdout), and putc can be implemented as a macro, whereas fputc cannot be implemented as a macro.

Line-at-a-Time I/O

Provided by two functions, fgets and gets.

#include <stdio.h>

char *fgets(char *restrict buf, int n, FILE *restrict fp);

char *gets(char *buf);

Both return: buf if OK, NULL on end of file or error.

Both specify address of buffer to read the line into. gets reads from standard input, whereas fgets reads from specified stream. With fgets, we have to specify size of buffer, n, function reads up through and including next newline, but no more than n-1 characters. Buffer is terminated with null byte. If line, including terminating newline, is longer than n-1, only partial line is returned, but buffer is always null terminated. Another call to fgets would be necessary.

IMPORTANT TIP

Never use gets. This function doesn’t allow caller to specify buffer size. Allows buffer to overflow if line is longer than buffer, writing over whatever happens to follow buffer in memory. Even if ISO C requires an implementation to provide gets, use fgets.

Line-at-a-time output is provided by fputs and puts.

#include <stdio.h>

int fputs(const char *restrict str, FILE *restrict fp);

int puts(const char *str);

Both return: non negative value if OK, EOF on error.

Function fputs writes null-terminated string to specified stream. Null byte at the end is not written. This need not be line-at-a-time output, since string need not contain a newline as last non-null character. Usually, this is the case but not required. puts function writes null-terminated string to standard output, without writing the null byte. But puts then writes newline character to standard output. puts is not unsafe like its counterpart gets, but we’ll avoid using it. If we always use fgets and fputs, we know that we already have to deal with newline character at end of each line.